Last week, many of us in the U.S. were bombarded with boisterous urgings to have a merry Christmas. As I recall, the British version is “Happy Christmas!”, while the French wish one another a joyful Noel (assuming my high school French is accurate). Even those of us who never studied Spanish know “Feliz Navidad” from the song; the internet tells me that “feliz” can mean happy, blissful, or felicitous. In the midst of these determinedly cheerful greetings, some Christians will wish one another a blessed Christmas, but for the most part, our traditional holiday wishes are energetic and robust.

For too many, this was a hard year. Unnecessarily hard, one might say, since so much of the hardness could have been avoided or mitigated. Unavoidably hard for others, where circumstances beyond their control led to grief and heartache that will henceforth be constant companions, simmering beneath the surface of whatever joy or pleasure they may one day feel.

By nearly any standards, I got off easy. My family and friends have come through the year largely unravaged by covid or other crises. My aging parents require increasing care, but everyone plays their part, and resources enable us to include hired assistance in the mix. My workload has been uneven, but small business funding supported me through the months when I would otherwise have relied heavily on credit lines to make ends meet. For the first time, my writing income has nearly offset the expenses incurred in creating and marketing the work.

And yet, by the last several weeks of 2021, my mind clicked along at such a frenetic pace that I found neither time, energy, nor inclination to sit and think creatively. The notion of writing a holiday blog post flashed through my brain, but I truly had no idea what to say. More troubling, literally every day I found myself turning over in my mind the plot line of my next book. I struggled to see how it will work out, to no avail. I’m terrified that it will disappoint those who have told me how they loved State v. Claus. As I raced from hither to yon, multitasking brilliantly, juggling all the balls high into the air, doing my utmost to create a marvelous holiday filled with light and music and joy, I often felt as if I were skating along the surface. I did all the things, but actual thought, actual deep feeling—this somehow was lacking.

And then, Santa made me sick. Literally.

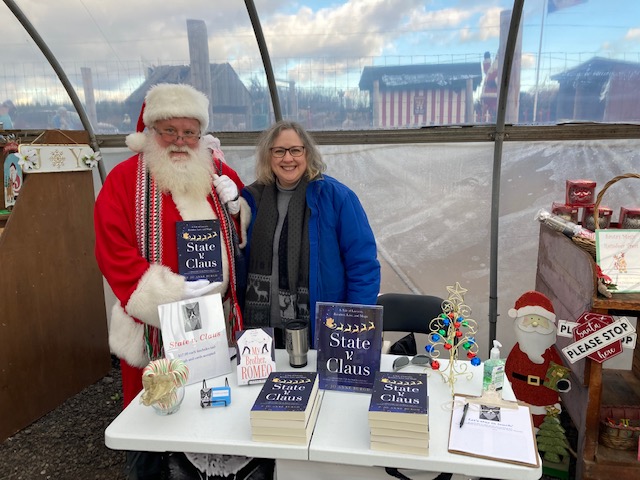

At least, I assume it was Santa. He was the only person with whom I had a close-up conversation of several minutes’ duration on the day before I began to feel ill. Fool that I was, I didn’t remember to put on a mask. I know he wasn’t wearing one, because I was close enough to see that his white whiskers were genuine.

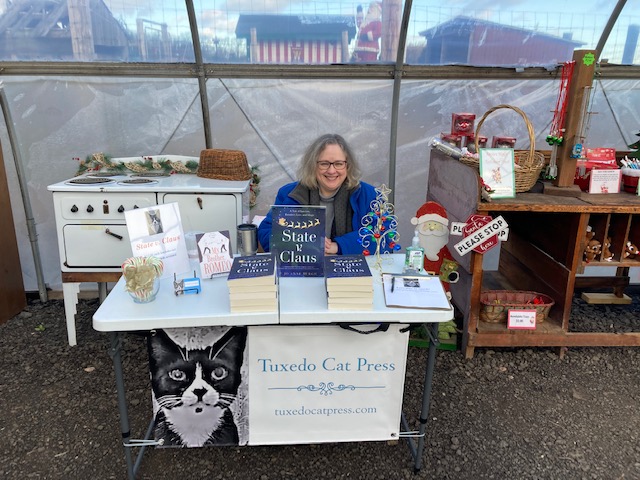

We were both at a local Christmas tree farm on a breezy Sunday. I was selling and signing books; he was welcoming children. My table was in the greenhouse where the Christmas tree shop had been set up, while he was located at a flagpole a little way down the parking lot. The greenhouse’s plastic that fluttered in the brisk wind. Mrs. Claus (who was indoors) occupied a chair several feet from my table. The checkout counter for regular shop patrons was on the other side of the greenhouse, easily twelve feet away. After Santa left, I did remember my mask, and I wore it whenever customers came in. Afterward, when I went with friends to the Lessons and Carols service at church, we all wore masks inside, shedding them only when we went outdoors afterward.

The next day, my throat felt scratchy. My sinuses felt congested. I immediately recalled my unmasked conversation with Santa and wanted to kick myself. Two days later, I developed a low-grade fever. I called my pulmonologist and left a message asking if I needed to be tested. My primary care physician’s office agreed that testing would be a good idea, but they had no available slots that week. With some effort, I tracked down a pharmacy where–if you knew to ask–you could purchase one of the home tests they had stashed in an unmarked carton behind the front register.

Blessedly, the test (performed on two consecutive days) was negative. Whatever this coughing/sneezing/congested/feverish thing was, it wasn’t covid. My pulmonologist put me on the usual course of antibiotics and steroids, just in case. Assuming reasonably that nobody else wanted whatever I was carrying, I cancelled a weekend’s worth of events, including a book signing, a client’s holiday party, and my regular trip to my parents’ house with Sunday lunch.

And then, I rested.

Amazing, isn’t it, how ill health is nearly the only thing that makes a person feel entitled to rest. Short of a physical “I can’t,” we push on ceaselessly against the waves, showing up, doing and being good, noble creatures who fall into bed exhausted, only to greet the next day with streams of to-dos running through our heads before our eyes are fully open.

I told myself I was doing everyone else a favor by staying away from them. While this was likely true, the real favor was to myself. I spent a dark, rainy Saturday in my pajamas, curled up in my favorite chair with a cup of tea and a library book, basking in the glow of the Christmas tree. In the background, soft holiday music played. Periodically, one or another of the cats would hop up into the chair, cuddling with me or settling in for a nap on the headrest. Since bronchial issues precluded a wood fire in the fireplace, I opted to light a candle, and the scent of balsam and cedar drifted through the peaceful room.

Christmas has come and gone. It wasn’t perfect, of course, but it was fine. On Christmas Eve morning, I allowed myself a few minutes to wish I could just stay home before packing up the gifts and the makings of several meals and toting them over to my parents’ home. The usual family dynamics ensued, but eventually I was able to return to my peaceful home where I poured wine and sat beside the Christmas tree, opening presents sent by my wonderful friends. Most of the gifts involved rest, relaxation, and beauty in various forms—teas, snacks, candles, books, artisan crafts, and luxurious soaps. The next day, I returned to the family gathering, augmented by my nephew and his companion, a photographer whose work often focuses on what can be discovered by looking at life up very, very close. By the time I got home, I was too exhausted even to nap beneath the wonderfully soft throw that was a gift from my sister.

I can’t say whether my post-holiday fatigue was due to stress or simply to the remnants of my Santa-induced illness. All I know is that on Sunday, as I granted myself another day of rest, words and ideas began to return.

I’d picked up another library book, The Fortnight in September by R.C. Sherriff. I spent much of the day reading about the Stevens family, a nice suburban family in early twentieth-century England who traveled each September to the seaside town of Bognor for a two-week vacation. Nothing particularly dramatic happens in the book; no arguments or clashes occur between family members. Even their occasional disagreements or disappointments are presented simply, as things that happen rather than emotional turning points or cliffs to be fallen off.

The Fortnight in September was published in 1931. It occurred to me as I read that if someone were to submit it for publication today, it would likely be rejected because it doesn’t hit any of the now-mandatory marks. It doesn’t begin with a hook. No great suspense builds for any character. The Stevenses don’t arrive at Bognor until nearly a third of the way through the book, the first part being taken up with their preparations the night before departure and the journey to the sea. Even the daughter’s brief holiday romance arrives late in the book and is every bit as swift as one might expect for a relationship lasting only a few days. The book might pass for literary fiction by virtue of the characters’ introspection, but other than that, it seems unlikely that this lovely little volume would generate much of a stir.

And yet, it did for me, and precisely because of its gentleness. The Stevenses are nice people. Not perfect, but nice. They aren’t fancy, a fact with which the son struggles briefly when it comes his time to be at the center of the story. Mrs. Stevens is primarily concerned about making her family happy, and her favorite hour of the day is in the evening when the others have gone down to the promenade and she sits in their rooms with her “medicinal” glass of port. The Stevenses are kind to people they see as less fortunate, including the neighbor who cares for their canary during their absence and the landlady at Bognor whose increasingly rundown house is noted, but not commented upon or complained about. When they splurge on a hut with a balcony for their days on the beach, the family truly appreciates this luxury, allowing themselves the smallest satisfaction of having such a superior accommodation. When they are invited to tea at the home of Mr. Stevens’s company’s client, they are excited to be seen being picked up in a private car, but they are not made jealous by the client’s fancy vehicle or his ostentatious home—in fact, they decline a ride back to their lodging, choosing to walk.

This republication of the book include an afterword by the author. At the time he wrote The Fortnight in September, Sherriff was renowned for his play, Journey’s End. Unfortunately, the success of Journey’s End was followed by two plays which, as Sherriff described them, “went down the drain.” He described the impetus for this, his only novel, and how in the end, he essentially had to get out of his own way, breaking himself of the habit of using “flowery stuff and highfalutin words” to describe this family.

Then, he wrote this:

~~~~~

The attraction of the story was that I didn’t lay out any plan and never knew what was going to happen in the next chapter until I came to it. It kept me in sympathy with the characters, because when they went to bed each night they knew no more about what was going to happen the next day than I did when I turned out the light on my desk and went to bed myself.

~~~~~

In other words, he was a discovery writer. A pantser, not a plotter.

I’ve been trying for so long to plot my next book that I forgot one basic truth: this isn’t how I write. I don’t outline or plan my stories. I write to discover them. And yet somehow, I’d lost faith in my ability to follow my characters through their issues and struggles. R. C. Sherriff reminded me that it’s enough simply to go along with the characters and see what happens.

It is, I think, no coincidence that in the midst of reading Sherriff’s novel, the ice began to crack in my writer-brain. Perhaps because I was allowing myself to rest, or perhaps because I was accompanying this pleasant family on an unexciting vacation, I couldn’t say. All I know is that ideas bubbled to the surface. In a spiral notebook, I jotted words and phrases as they came, not censoring or rejecting any as inconsistent with mood or themes. I treated my notions gently, neither probing nor judging. And so they began to flow once more.

At one point in the flood of online holiday greetings, I happened upon one that wished everyone a gentle Christmas. When I read this, longing welled up in my soul for such a holiday, filled with stillness and kindness, beauty and love.

In the most unexpected way possible, Santa gave me precisely this gift. By transmitting a few germs—just enough to incapacitate—this gentleman bestowed on me the precious gift of unassailable solitude where I could rest, free of the demands even of my own mind. Instead of consuming irritating online content about current events, I read other people’s graceful words in physical books as winter rains tapped the window and cats snuggled in the chair with me. Those words freed up my own, enabling me to move forward gently, trusting that wherever the story comes out is just where it ought to.

Thanks Jo for reminding us that we don’t have to be busy to be satisfied and happy. There is a calmness in your post that is comforting, familiar and so very welcome. Happy New Year!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Diane! Happy new year!

LikeLike

Fascinating post. Some random observations: #1 “Santa Unmasked” sounds like a good subject for a Christmas short story! #2 In the UK probably the most common blessing over the festive season is to wish someone “A merry Christmas and a happy New Year”. In this context the word “merry” usually implies an alcohol-fuelled glow, so I can’t understand why we don’t also wish people a Merry New Year too given the amount of alcohol traditionally consumed on New Year’s Eve 🙂. #3 Sherriff’s book sounds like a fascinating sketch of middle-class life in the south of England nearly 100 years ago. Isn’t it interesting how, with the passage of time, contemporary observational pieces morph seamlessly into revealing historical insights.

Anyway, enough of this drivel. I hope your writing goes well in 2022, and that you enjoys lots of cuddles with the cats 😺. Best wishes to you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much, Platypus Man!

I forget now where I heard that “Happy Christmas” is the traditional British greeting. Here in the U.S., Christmas greetings are pretty much the only time we use “merry” at all—nobody talks about having had a merry time at a party or whatever, which makes me wonder why it’s hung on for Christmas.

Sherriff’s book is indeed fascinating. It caught my attention because of its cover blurb from Kazuo Ishiguro, who called it uplifting and life-affirming, and that sounded like exactly what I needed. Definitely worth the time for anyone looking for a gentle read.

The cats and I wish you a happy or merry (your choice) new year!

LikeLiked by 1 person

An endorsement by Kazuo Ishiguro says it all. I’ll look out for a copy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

All my British friends say “Happy Christmas” so you’re not alone in that belief. I recall the first time I heard that expression was in 1968 when I spent Christmas through New Year’s Day in the UK.

Had to laugh when you said you don’t outline because I remember that outline challenge you issued nearly 10 years ago. It was a struggle, but I did it!

Best wishes for continued success in the new year.

P.S. Love your tree!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Dee! (It’s ever so much easier to issue a challenge than to perform it, so brava! 👏🏻👏🏻👏🏻)

LikeLike